For those who were born before the 2000s may recall picturesque houses with slate roofs in the villages, particularly in parts of the eastern Nagaland region. The slate roofs stood like soldiers – grey strong and beautifully aligned, but beneath those roofs, life was simpler and traditional.

Slate-roofed houses have long been regarded a unique cultural identity of the Khiamniungan people, the Pochury of Meluri district and the Yimkhiung in Kiphire district, although the practice is diminishing.

In the olden days, Khiamniungan houses were generally of two types – those with thatched-roof and the other with slate roofing, the latter being more prominent and considered prestigious. The practice of roofing with natural sheets of slate, known locally as Lungkhaiustam (meaning “slate roof house”), was deeply rooted in the community’s way of life. These flat rocks, typically found in shades of grey and dark grey, were used not only for residential houses but also for morungs (traditional dormitories) and granaries. Slate roofing, in fact, preceded thatch in many villages. Today, however, it has become a thing of the past.

Download Nagaland Tribune app on Google Play

A Living Memory in Peshu

About 15 kilometres away from Noklak town lies Peshu village, a place of antique charm. Its houses, roofed with slate, stand as living monuments to a fading heritage. No one recalls exactly when these houses were built, yet they have withstood the test of time. The villagers continue to repair them with care, their hands preserving what history has left behind.

Travelers who pass through Peshu pause in awe, taking shelter under the cool shade of these antique roofs, marvelling at how seamlessly the slate-roofed houses blend with the surrounding landscape and village paths.

One of the few surviving slate stone masons from Peshu, Pesing recalls how in olden days, rituals were performed to deities before cutting the slate- so that the rock would split into the desired shape. “Now, we begin our work with prayer,” he says.

One of the last surviving roof slate craftsmen

The craft of slate-cutting is far from easy. According to Pesing, it can take an entire day to shape just a few pieces, using only a chisel and hammer. The quarry, located deep in the hills without electricity, makes it impossible to bring in machines. Hence, the builders continue to work the slates manually with patience and skill they have mastered over the years.

A quarry where slate is extracted for constructing roofs

Echoes of a Vanishing Art

Do the younger generations look upon these houses and feel inspired by the genius of their ancestors? In an age of concrete, CGI sheets and modern designs, the old skills are fading fast. Yet, amid this change, some young people still dream of rebuilding slate-roofed houses- not merely for nostalgia’s sake, but as an act of remembrance.

Slates after they are extracted, cut, shaped and ready to use

For them, to rebuild such traditional slate roofed houses is to remember who they are – a people whose hands once shaped rocks into homes, and whose legacy still whispers through the slate roofs of Peshu.

What does the future hold?

Preserving these houses poses challenges. Slate is heavy and difficult to transport, while modern materials are cheaper and easier to maintain. However, as tourism gradually reaches Noklak, the slate houses of Peshu could become a centrepiece of cultural heritage. They offer not only aesthetic beauty but also lessons in ecological design—built entirely from local, biodegradable materials, requiring no imported resources.

There is growing interest among young Khiamniungan scholars and artists to document and revive traditional architecture. Because when a roof of slate falls, it is not only rock that breaks, but it is memory.

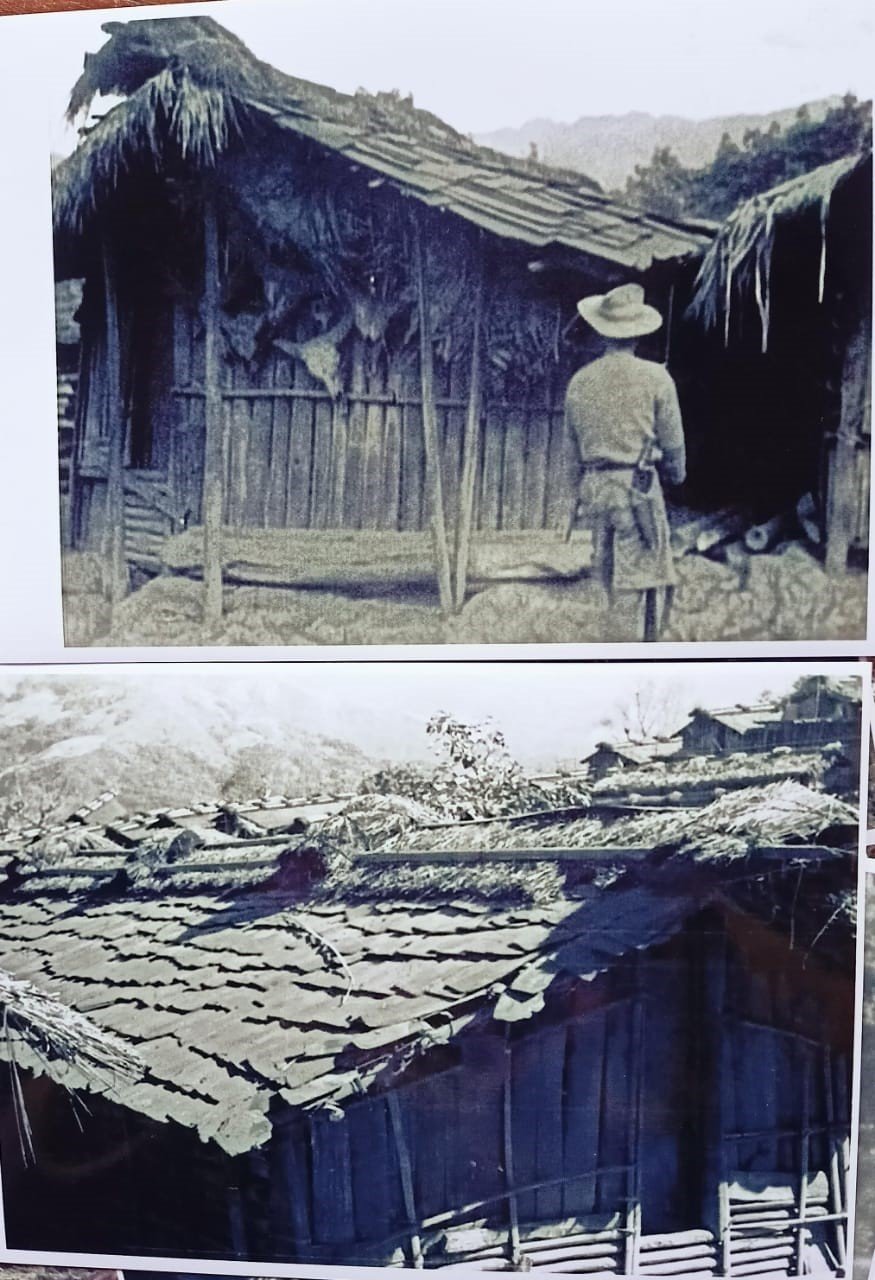

Noklak Village in the year 1936 photographed by Christoph Von Fürer-Heimendorf.

(From the archive of Buhiu B Lam’s library)

To the untrained eye, they are only stones. But to those who listen, they speak of a people who built not just homes, but heritage layer-by-layer, with patience and love.

The true beauty of Peshu’s slate houses lies not merely in their endurance, but in what they remind people- that culture is not frozen in time, but it lives in the hands that build one sheet of slate at a time.

–This is the third of a four-part series of reports on the construction sector in Nagaland written as part of the Kohima Press Club-Nagaland Building and Other Construction Workers Welfare Board (KPC-NBOCWWB) Media Fellowship 2025.