Author: Dr Vinod Balasubramaniam is an Associate Professor of Molecular Virology and Leader of the Infection and Immunity Research Strength in the Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences at Monash University Malaysia.

While the Indo-Pacific has been one of the regions least affected by mpox in the past, that could change if the virus spreads unchecked.

Once thought to be mainly contained to Africa, cases of mpox (previously known as monkeypox) have been detected in Sweden, Pakistan and the Philippines over the last few days.

This follows the World Health Organization’s decision last week that the recent upsurge in mpox cases warranted it to be declared a public health emergency of international concern, highlighting the rapid spread of the virus and its potential for severe health impacts.

The last time this happened was in July 2022.

Of particular concern, testing has revealed the case in Sweden is the more virulent clade 1b subtype, the first time the strain has been detected outside Africa.

It’s only a matter of time before mpox cases increase across the Indo-Pacific, although the WHO is stressing we know a lot more about this virus and how it spreads than we did about COVID-19.

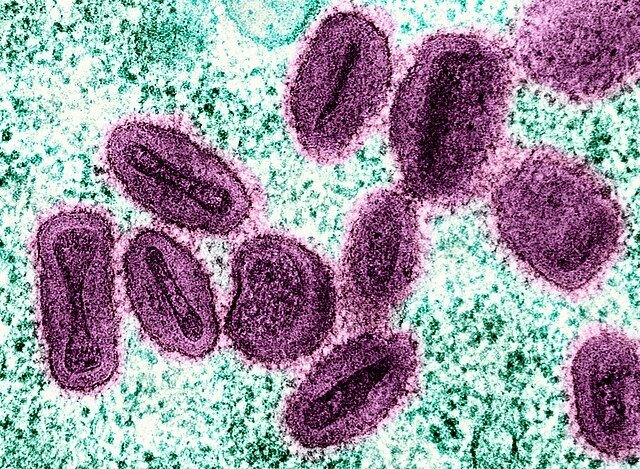

Mpox is an infectious disease caused by the monkeypox virus, which belongs to the orthopoxvirus genus. This genus — or family of viruses — also includes the variola virus, the virus that causes smallpox.

The first documented case of mpox in humans was reported in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Since then, mpox has been classified into two primary clades: clade 1, previously known as the Central African strain, which is more virulent; and clade 2, previously known as the West African strain, which is generally less severe.

Historically cases of mpox were rare outside of Africa, however a significant global surge in cases began in May 2022 and has been followed by another increase this year, as the number of cases in Australia shows.

How mpox is spread

The transmission of the monkeypox virus occurs through several primary routes, with human-to-human transmission being the most significant.

This transmission typically involves direct contact with the lesions or bodily fluids of an infected individual, particularly during intimate interactions.

Respiratory droplets can also facilitate transmission during prolonged face-to-face contact. Additionally, fomites — contaminated surfaces — can serve as vectors for the virus.

Animal-to-human transmission remains a critical route, often occurring through direct contact with infected animals, such as rodents or non-human primates, particularly in regions where bushmeat is consumed. Vertical transmission from mother to fetus during pregnancy has also been documented.

The epidemiology of mpox has notably shifted since the outbreak in May 2022, with a marked increase in cases reported among men who have sex with men, indicating a change in transmission dynamics.

The clinical presentation of mpox includes symptoms such as fever, lymphadenopathy (swollen or enlarged lymph nodes) and characteristic skin lesions. One good thing for now, is that people with mpox can only transmit the disease when they are showing symptoms.

Although mpox is less lethal than smallpox, it still poses significant health risks, particularly to vulnerable populations.

Recent outbreaks and the global response

The emergence of mpox cases in non-endemic regions has raised concerns about public health preparedness.

Countries like Australia are enhancing surveillance and public health education to monitor potential cases and prevent outbreaks. China will be monitoring people and goods entering the country for mpox for the next six months, it announced last week.

The WHO’s designation of mpox as a public health emergency underscores the urgency of addressing the disease’s potential for rapid spread, particularly in populations with low immunity due to the end of smallpox vaccination programs.

In Australia, where widespread immunity against orthopoxviruses is lacking, vigilance is essential to mitigate the risk of mpox entering the country, especially through international travel.

The recent emergence of the more virulent clade 1 strain of mpox raises significant concerns about its potential to escalate into a global pandemic, particularly in the Indo-Pacific region.

This strain has been linked to higher mortality rates and increased transmissibility.

While the Indo-Pacific has been one of the regions least affected by mpox in the past, due to its interconnectedness and varying healthcare capacities, it could face substantial risks if the virus spreads unchecked.

The appearance of clade 1 in Sweden indicates that the virus can cross borders easily, posing a threat to countries with less robust public health infrastructure.

Current treatment options

Vaccination strategies for mpox significantly differ between its two primary clades, clade 1 and clade 2, due to variations in virulence, transmission dynamics and outbreak contexts.

Clade 1, endemic to Central Africa, has a historically higher mortality rate of up to 10 percent and is primarily transmitted zoonotically — from an animal to a human — with limited human-to-human spread.

By contrast, clade 2, particularly the subtypes clade 2a and 2b, has a lower mortality rate of about 3.6 percent and was responsible for the global outbreak that began in 2022, spreading predominantly through human contact, especially within sexual networks.

Vaccination efforts for clade 1 target high-risk populations in endemic regions, emphasising rapid vaccination following exposure.

Vaccines such as JYNNEOS and ACAM2000 originally developed for smallpox, are expected to provide cross-protection against clade I mpox, although specific efficacy data is limited.

Public health education on zoonotic transmission is also crucial to prevent outbreaks.

For clade 2, vaccination strategies have been more aggressive, especially for clade 2b, with vaccines like JYNNEOS deployed in non-endemic regions targeting men who have sex with men and other high-risk groups.

This includes both pre-exposure and post-exposure prophylaxis, supported by global efforts to establish vaccine stockpiles and ensure equitable distribution — particularly in Africa where shortages have been reported.

Antiviral treatments such as tecovirimat have been found to be ineffective, highlighting the need for urgent further research into effective therapeutics for mpox management.

Where do we go from here?

The current global mpox outbreak has underscored critical lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in the areas of communication, equity and preparedness.

Effective responses require clear, empathetic communication to build trust and reduce stigma around the disease, especially among marginalised communities disproportionately affected by outbreaks.

Rapid containment measures, including case identification, contact tracing and isolation, have proven essential in managing spread, mirroring successful strategies from COVID.

The COVID pandemic highlighted the importance of leveraging technology for information dissemination, ensuring equitable access to resources.

A coordinated government response is vital, emphasising collaboration across all levels of public health agencies to address emerging inequalities.

The necessity of stockpiling vaccines and ensuring their equitable distribution has become evident, as seen in the challenges already faced during this mpox outbreak.

The most effective strategy right now is to send mpox vaccines to Africa to try and stop the disease from spreading.

Vaccination campaigns must be comprehensive and community-engaged to enhance uptake and address vaccine hesitancy.

(This article is republished from 360info under Creative Commons licence.)