Author Satish Kumar is Research Fellow, The Senator George J. Mitchell Institute for Global Peace, Security and Justice, Queen’s University Belfast and Chairperson- Kerala Urban Policy Commission and Distinguished Honorary Chair of Global Sustainable Development Goals at the Techno-India University, Kolkata.

The recent Indian election saw prime minister Narendra Modi re-elected for a third consecutive term, although his party, the BJP, failed to secure a majority in the lower house of parliament.

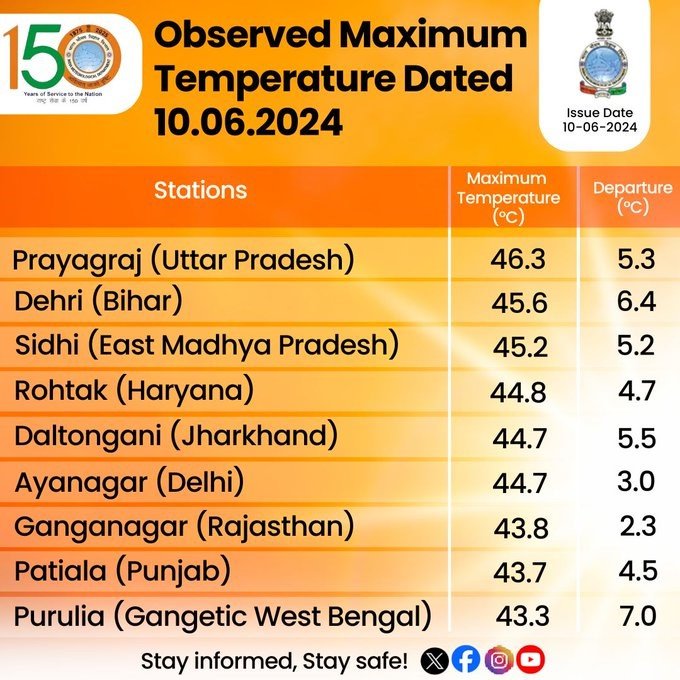

This election season was characterised by severe heatwaves, which have already killed at least 200 people and are likely to happen many times more often as the world keeps warming.

All the major parties made various climate pledges. The BJP, for instance, stressed the importance of green industry and energy, and targeted 500GW of renewable energy by 2030, while the opposition Congress party had its own renewable targets and proposed creating an “Environment Protection and Climate Change Authority”. But, despite all this, climate change did not become a major issue.

This is likely to change in the near future. As the election dust settles across the subcontinent, and further heatwaves arrive, talk of the right to a fan, a cooler, ice and aircon will only intensify. How to communicate the critical challenges posed by climate change to the people of India remains an abiding question that transcends any single election.

For now, what some in India refer to as the “brown agenda” still trumps the “green agenda”. The brown agenda refers to meeting the basic needs of a community, such as food, clothing and shelter. Where it overlaps with environmental issues, it tends to focus on things like safe drinking water, sanitation and drainage, and the transition from low-grade domestic fuels.

Pre-poll surveys in India indicated that employment, inflation and taxes remained the key concerns. Even among millennials climate change was only the fourth most important issue. No wonder then that elections across the subcontinent still focus on caste, religion and identity at the expense of a “green alternative”.

Where a green agenda has emerged it is as a result of the Indian economy transitioning from a subsistence rate of growth to one of the fastest growing in the world. Some environmental issues are being camouflaged as social or welfare issues. For instance, given about half of the population are still engaged in the farming sector, which is already provided subsidies for water, fertiliser and price guarantees for its produce, there is a renewed demand for key waterbodies to be protected from pollutants caused by rapid industrialisation.

Identifying water sources for farming remains critical. The political parties have focused on the immediate needs of their constituencies be it access to water, sanitation, waste management or preserving the environment, without necessarily labelling it as an environmental agenda.

A collective and democratic response

India remains one of the countries most vulnerable to climate change. It is estimated that 8% of GDP was lost due to rising temperatures and climate-driven extreme weather and there is a growing burden on public health.

To become “climate-smart” and ready for even more extreme weather, India must come to appreciate that ecological poverty is as important as economic poverty. And ecological survival is only possible with collective and democratic responses to both the brown and green agendas. That will probably mean further economic growth – the luxury of zero growth is a non-starter for the developing world.

At the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow in 2021, Modi stressed that India, with 17% of the world’s population, contributed a mere 5% to global emissions.

Lifting millions of people out of poverty remains a herculean task. Speaking after his recent reelection, Modi reaffirmed his dedication to ushering in a “green era” characterised by a synthesis of development and environmental sustainability.

(This article has been republished from The Conversation under Creative Commons Licence.)